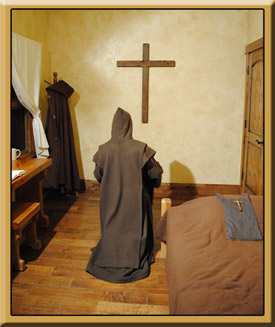

Our approach to prayer

‘God is present everywhere – present to the good and to the evil as well, so that nothing anyone does escapes His notice; that is the firm conviction of our faith. Let us be very sure, however, without a moment’s doubt that his presence to us is never so strong as while we are celebrating the work of God in the oratory. And so we should always recall at such times the words of the psalm: Serve the Lord with awe and reverence, and sing the Lord’s praises with skill and relish, and: I shall sing your praise in the presence of the angels. All of us, then, should reflect seriously how to appear before the majesty of God in the presence of his angels. That will lead us to make sure that, when we sing in choir, there is complete harmony between the thoughts in our mind and the meaning of the words that we sing.’

The Rule of Saint Benedict focuses very little upon the theory of prayer. If you pick up a copy hoping to find a quick fix to your spiritual life to turn you into a saint overnight then you are going to be bitterly disappointed. Chapters nineteen and twenty are the sum total of the teaching that is not about the mechanical workings of the liturgy. This is not because Benedict does not care, quite the contrary, but it is something that must be experienced and lived – something that becomes as natural to the monk as breathing.

The opening remark of this chapter, taken out of context, could give carte blanch to the seeker of a spiritual life to not take part in the rigorous liturgy with all the complicated seasonal changes – if God is everywhere, why both going to a special building and saying specific words? Surely my own private prayers, wherever I choose to offer them, are just as good?

But the second part of this chapter casts that idea aside. Yes, God is everywhere and yes He is available to those who are good and evil alike, that is His will, but that does not mean each of us are capable of offering true worship to God in the recesses of our own thoughts. The soul seeks – it seeks the ultimate meaning in life, which is God, but we are not always able to discern exactly the path that it should take. This is why, very often, people become entranced by different ways of attempting to satisfy that restless soul. As Saint Augustine said ‘Our heart is restless until it rests in You’ – Going to a particular place and making oneself attentive through particular words is not a magic incantation to summon God before us that we may commune with Him more effectively – it is a way to train the restless heart, soul and mind to pay attention to the work of the Divine that goes on in all places at all time and to catch a hold of it – to not tentatively dip our toe into the water but to plunge, head first, into the torrent and allow ourselves to be swept along with Him.

Benedict is very clear that we cannot simply go through the motions – the singing in choir must produce harmony – not only in the musical notation but in the connection between those beautiful words of scripture, the rawness and power of the psalms and the heart, mind, soul, and indeed, the very being of the Christian at prayer.

Why does Benedict not write much about the theory behind the practice of prayer? It is much the same as those who hunt for the memorial of Sir Christopher Wren and find the inscription in the centre of St. Paul’s Cathedral telling them to look around them. Pick up Benedict’s Rule and each chapter teaches that prayer is a lifelong and lived vocation.

When I left a Benedictine retreat last year I had a horrible anti-retreat in my soul afterwards. I’m sorry that I bitterly regretted that I could not still join the beautiful choir at St. Cecilia’s.

It was a struggle each time I was aware the Sisters were meeting to praise God.

Then during prayer I saw all those Psalms going up like incense to Christ crucified, soothing Him in His agony, and imagined all the Monasteries throughout the centuries prayers being united in one great moment of worship.

I felt, even in the bitterness of His passion, Christ was blessed by their love. (Religious communities are of course a more beautiful legacy than St. Paul’s Cathedral, but that’s just an aside)

I was delighted to be a part of their worship then, as a member of the mystical body of Christ, even if I couldn’t be a part of it directly.

Though equally called to a life of prayer, and even with the grace of contemplative prayer at this time, the call to enter and remain in the beauty of the Liturgy seems a higher one…

When you’ve experienced that I think it’s difficult to allow ourselves to get swept along, even when attentive and lovingly close to Christ, in another direction.

Speaking of prayer.. bedtime. Look forward to reading your Blog and learning more about Benedictine spirituality. God bless.

LikeLike